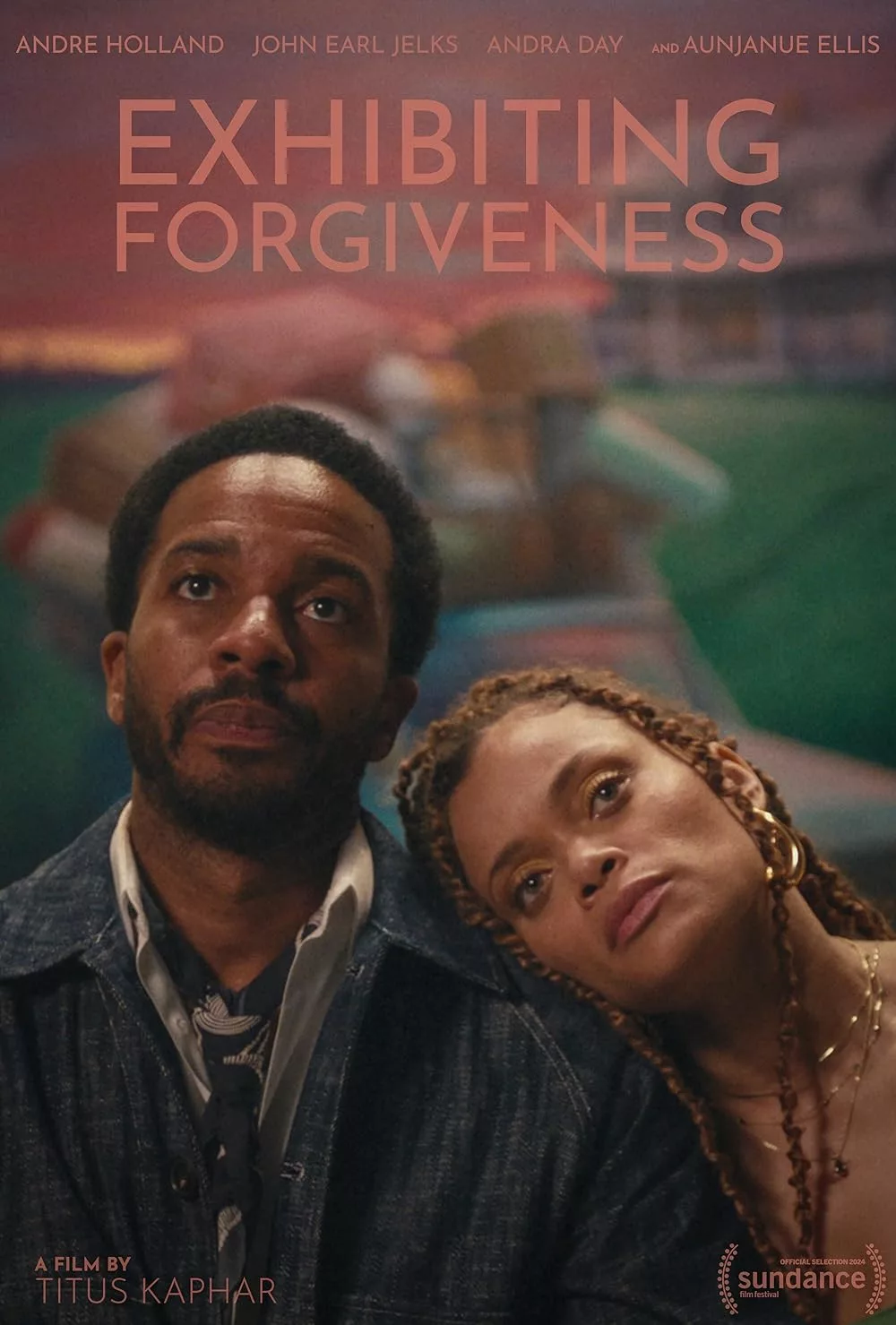

Visual artist Titus Kaphar has transitioned his creative mind to the screen as the writer-director of his first feature, "Exhibiting Forgiveness." Kaphar's body of work is defined by experimental form, with paintings hanging off other works, bunched up on top of them, or having pieces of their canvas slashed out. These layers and omissions are always meant to enhance elements of Black identity, whether through universality or subversion. Utilizing his own paintings as the backbone of the film, "Exhibiting Forgiveness" aims to accomplish the same, analyzing generational trauma and the links between fathers and sons in specific.

Tarrell (André Holland) is a painter. Having just concluded a successful show, his agent prompts him to ride the coattails of his current hype and host another. His work is time-consuming, and with a young son, Jermaine (Daniel Michael Barriere), and supportive wife, Aisha (Andra Day), who has put her musical endeavors on the backburner to give him the space to work, Tarrell is hesitant to dive back in. Not only do the hours of painting and prepping for a show take away Aisha's space to accomplish her goals, even more so, they limit the time he's able to dedicate to his son, and being a father is incredibly important to him.

When his own estranged father, La'Ron (John Earl Jelks), unexpectedly comes to visit him at his mother Joyce's (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) house, Tarrell is forced to confront feelings he'd rather leave in the past. Joyce, a highly religious woman, hopes that Tarrell and La'Ron can reconcile their checkered past, marred by La'Ron's abuse and addiction. But even though La'Ron has found God and pleads to show his son that he has changed, the demons of Tarrell's adolescence–memories that both wake him in the night as well as motivate him as a father–threaten his ability to forgive.

"Exhibiting Forgiveness" is a visual revelation. Cinematographer Lachlan Milne's ("Minari") photography is stunning from every shot to the next. Through his camera and Kaphar's direction, there is a clear influence from Kaphar's own paintings in the framing choices, but also an evocation of Gordon Parks' stunning tableaus. The portraiture of the film is equally romantic, with long takes and close ups allowing us to absorb the soulful performances that take "Exhibiting Forgiveness" to the next level.

Holland and Jelks are a duo that punch through the screen. Kaphar's screenplay builds its foundation on the slew of conversations that take place over the course of the film's runtime. These conversations often flirt with overstating their sentiments, but Holland and Jelk transform the words into heart-wrenching feeling.

Jelk's eyes alone project the volumes of La'Ron's guilt, love, and stubbornness, and the ways he's trying to package them for redemption. Holland, who feels criminally underused for leading roles after his groundbreaking performance in "Moonlight," often summons Tarrell through his body, giving a physical performance that lands an impact as much as his wordless expressions of hesitance and pain. Tarrell's self-soothing fidgeting and pacing evoke the young boy still alive within him trying to remain hidden from view, and Holland balances these conflicting identities with a gentle but assertive performance.

Kaphar utilizes Tarrell and La'Ron to tell a very personal familial story, whilst also inserting gritty intracommunity experiences that testify to Black fathers and sons. His narrative holds space to acknowledge that each past generation is one that is closer to the harshest parts of Black history, and that no man has survived it unscathed or without things to unlearn. At the same time, while Joyce and La'Ron each use God and the Bible as a constant means to nudge Tarrell towards forgiveness, Kaphar sharply criticizes religious absolution for absolution's sake. It is integral to its storytelling that "Exhibiting Forgiveness" provides empathy to La'Ron whilst landing far from the idea of exonerating him. This is Tarrell's film, one that gives love and credence to the idea that some things cannot be forgotten. Kaphar's film bloats its runtime, with a handful of conversations going back for seconds on a full stomach, but it still manages to be utterly moving, entrusting its cast completely with carrying its ideas to touching fruition.